THE DUTCH ARRESTED MY FATHER, MY UNCLE AND OTHERS, 1948

One day the painters of the Ministry of Youth and Development office called

many children, distributed papers, drawing tool and materials then requested the children to draw. The

drawings were collected and exposed on the office wall. Painter Soerono explained the meanings of the

drawings to the guests who came. The

children were very proud that their works were appreciated.

Picture 1:Painters taught children to paint in Bugisan 5 street Yogyakarta in 1948.

In these Republic of Indonesia struggling years,

the painters and the caricaturists worked to build enthusiasm to defend the

existence of the Republic with their own specific talents and methods. In front

of the State Building of Yogyakarta, one could read good lettering

graffiti with grammatically-right English

words. We Don’t Want to be Ruled by Any Other

Nations. There must be an

educated politician who dictating the words and painters who were trained in using the brush and wrote it on the

wall. Many more similar graffitis found everywhere in Indonesian towns.

There was also an undercover hand-operated printer in

Taman Siswa Street which printed

motivating slogans on easily torn rice-straw paper. Indonesian used any material possible to maintain its existence and spirit. Abdulsalam’s pro Republic caricatures were often published in the

Kedaulatan Rakjat, Nasional and Patriot newspaper in Yogyakarta (Blog Arswendo

Atmowiloto, Tiga yang Berharga, 19/07/2007).

At the neighboring house

near Bugisan street 5, every Saturday night 10 teenagers perform Orkes

Bambu or Bambu Band with bamboo flutes, blowed-bamboo bass, drums, and ukuleles. The singer was the most cute girl

in the kampong, Isti Karniah. Younger children flocks around the band as

spectators. They never thought that something dangerous would happened the next day.

On Sunday morning at 7 a.m. December 19, 1948 Dutch

Military Aggression (II) or named as Kraai

Operatie began. President Soekarno, Vice President Moh. Hatta, Sutan

Sjahrir, Agus Salim and many Indonesian leaders were detained and imprisoned.

Four hundred and forty two members of Korps Speciale Troepen, 2600 of M

Fighter Group and 1900 of T Fighter Group under Captain Eckhout attacked Maguwo

airport. Unmatched in numbers and armaments 128 persons of 150 West Java

originated Siliwangi Division were killed.

This was another breach of the Renville

Agreement which was conducted on January 1948. Renville is a name

of US ship where the agreement was conducted.

At the same day of the aggression to Yogyakarta,

Commander in Chief of Indonesian Army, General Sudirman ordered Siliwangi

Division to come back to West Java to strengthen their original area. Another General Sudirman's order which was printed at the back of the postcards published by the

Republic said: “Defend your homes and yards”.

Picture 2: Siliwangi Division members with families walking 600 km went back from Yogyakarta to their origin territory of West Java at night to avoid ambush by the Dutch.

One day after the offence, Abdulsalam’s family,

Soerono’s family, Oesman Effendi, Soedibjo and our extensive family fled to the

village of Cebongan still in Yogyakarta recidency.

Our extensive family consisted of our core family that

was my father and mother, my younger sister Isti, my younger brother Yanto plus

my grandfather Wirjo, my two aunts Suwarti and Supiah plus two maid servants

Kasiyem and Yatin, who didn’t have time to go home to leave us when the Dutch

attack happened.

Abdulslam’s

extensive family was Abdulsalam and wife, Wiwi, their children Wibowo and Nani

and a maid mbok Hardjo. The journey to Cebongan was a very hard for a kid of my age and

under because it was hot, far, and no food to eat and we have to move fast

because we have to arrive at Cebongan as soon as possible. To make matter more

torturing, the flee was not straight but had to circle south-west part of

Yogyakarta to avoid streets and areas that we considered had been occupied by

the Dutch.

At the cross road west of Pingit we saw three corpses

and a black sedan car damaged. We walked quickly passed the horrified scene.

We arrived at the house of Kambali at Cebongan around 2 pm.

Without any sound, suddenly, early in the morning four

Dutch soldiers, came and captured Abdulsalam, Usman Effendi, Soedibjo, dan my

father Abdullah Angudi. They were marched to Cebongan sugar factory which has became

headquarter of the Dutch platoon.

Picture 3: Abdullah Angudi, Abdulsalam (painter), Soedibio (painter) and Oesman Effendi (painter) were arrested by the Dutch at Kambali's house at Cebongan.

During this invasion Minister Soepeno, the minister who

subordinated the Bugisan office and those painters was also arrested by the

Dutch and was shot. After the war the name Minister

Soepeno became the name of streets

in Semarang, Yogyakarta and other towns.

Picture 4: Minister Soepeno was caught and shot by the Dutch

Soerono and others who went to the river nearby to take

bath were not aware that his friends had

been captured. They were frightened and worried when they got home.

Next morning led by Soerono, the only young man in the

group, the refugees walked to the next uncertain destinations. The move didn’t

take long and we arrived at the kampong

of Kontengan. We found only some damaged large huts with rotten bamboo walls as

our shelters. It was cold at night. Wind blowed through the holed walls.

In the meantime after two nights at the detention chamber at Cebongan sugar factory, Abdulsalam, Oesman Effendi, Soedibjo and my father were brought with a truck to Ngupasan jail behind the State Building in Yogyakarta. All were alive because the truck which carried those prisoners from Cebongan to Yogyakarta was not ambushed by the Indonesian guerrillas or National Indonesian Army, TNI.

During many days of the interrogation sessions at Ngupasan, Dutch

soldiers didn’t find any clues that

Abdulsalam and my father were members of the guerrilla and hence they were not

badly treated. Praise to Allah (Glory to Allah) that the

Dutch didn’t find any connection of my father with Temanggung where my father

was one member of the demolition guerrilla team. Also probably my father didn’t

tell the Dutch that he had ever lived in that town.

Among the inmates was the mayor of Yogyakarta, Mr. Soedarisman Poerwokoesoemo.

After one week in Ngupasan jail, my father was released.

Once again my father walked to Cebongan passing different, very deserted,

dangerous and strange route my father never walked through before.

Unfotunately somewhere outside of town, at a village cross road, my father was

encountered by a group of patrolling Dutch platoon. They circled my father and detained my father and

asked who my father was. My father explained in Dutch that he just been

released from Ngupasan jail that very morning. My father learned Dutch language

in the Dutch-Indie Elementary and Secondary School and that helped the Dutch to

be lenient to my father. The Dutch soldier made a radio call to Ngupasan jail

to confirm my father’s explanations. Then the Dutch patrolling soldier released

my father and let my father go. It was a very tense moment because my father

had heard the fate of my uncle, Adi, who was captured, ordered to go and shot dead from behind.

My father went further and about one kilometer from

where my father was asked by the Dutch, he was stopped by a group of

guerrillas. The guerrillas asked what my father had talked with the Dutch

patrolling soldiers. My father explained the guerrillas, the story from the

capturing at Cebongan till the releasing from Ngupasan jail.

The Indonesian guerrillas were suspicious to every

person coming from town, because coming to the villages from town was Dutch

spies’ routes. The Indonesian Dutch spies usually came as a cheap cosmetic

peddlers as covers at market days . They could also tell fake

stories about themselves when asked by the guerrillas.

TNI believed my

father’s story and my father was allowed to go to Cebongan to find his family. In the case of Indonesian guerrillas didn’t believed

my father’s information and looked upon it as a fake story, they could execute

my father easily.

The village roads were void of people and everybody

were afraid of being asked by strangers. They were frightened if they talked

with a stranger because he or she might

be a Dutch spy. If you were suspected as

a Dutch spy, since your answers were vague, you could be killed easily.

But at last my father found us after asking many

villagers whether they saw a group of refugees with certain number and

characterictic of the group passing their villages.

Meanwhile at the same day when Yogyakarta was invaded

by the Dutch, West Java originated Siliwangi Division was ordered to go back to

their area. But since the locations where the troops and their families were

staying in Yogyakarta were separated in too many buildings and people’s houses, the order could not be done

fast and simultaneously. Disseminating

the order and to determine the places and

time of meeting for departing together was done from mouth to mouth for

secrecy.

Many main roads and infra-structures were occupied by

the Dutch and so Siliwangi movement was executed only by night walking for 500 km to West Java

trough rice field, country paths, villages, crossing rivers in the rainy season

of Java. Nobody prepared the provision except very poor farmers of Java who took pity to the groups who were consisted of man, old woman, pregnant and children. This long torturing journey was named The

Long March of Siliwangi.

At last my father found us and the group in the kampong

of Kontengan. Then we moved on to Jumeneng Alit.

At Jumeneng Alit in the evening when I played with my

new buffalo-shepherd friend, we were

suddenly in the middle of a cross-fire between the guerrillas and the Dutch. My new friend and I squatted in a cluster of bamboo trees.

Running guerrillas jumped above our heads. Because the Indonesians had only

limited ammunitions, they usually fired some shots to the Dutch and run, they

never made frontal fightings. They never ambushed the Dutch in the morning but

at the late evening when the Dutch were exhausted from patrolling. Bamboo trees

around us hit by bullets broken, creaked

and collapsed.

When I went home I was reprimanded by my worried father

and mother since I was playing too far apart and this could be dangerous since I might be

lost when the refugees had to move on.

Being aware that

Jumeneng Alit was not safe, the rest of the group went west and arrived at the

village of Bligo, outside Yogyakarta regency, near Progo River. Since the end

of evacuation was vague, while the provision was depleting, Soerono and his

wife and their children Widodo, Soerojo and Tuti decided to go back to

Yogyakarta. We separated at Jumeneng Alit.

At Bligo, a rich

farmer named Mangunredjo accepted us and he prepared three rooms and other spaces

for us.

Three weeks later Abdulsalam who was released from Ngupasan jail

walked to Cebongan, Kontengan, Jumeneng Alit and Bligo, through unfamiliar,

strange and deserted tracks. The routes `mentioned above was hiked thru frequent askings to the alarmed villagers. This method made Abdulsalam found the

way to Bligo and found us.

...and do no evil nor mischief on the (face of the) earth.

(Koran 2:60)

(Next episode:The Retreat of the Dutch, 1949 at angudi003.blogspot.com).

Sardjono Angudi

11/2012 revised 11/2015 revised 02/2023

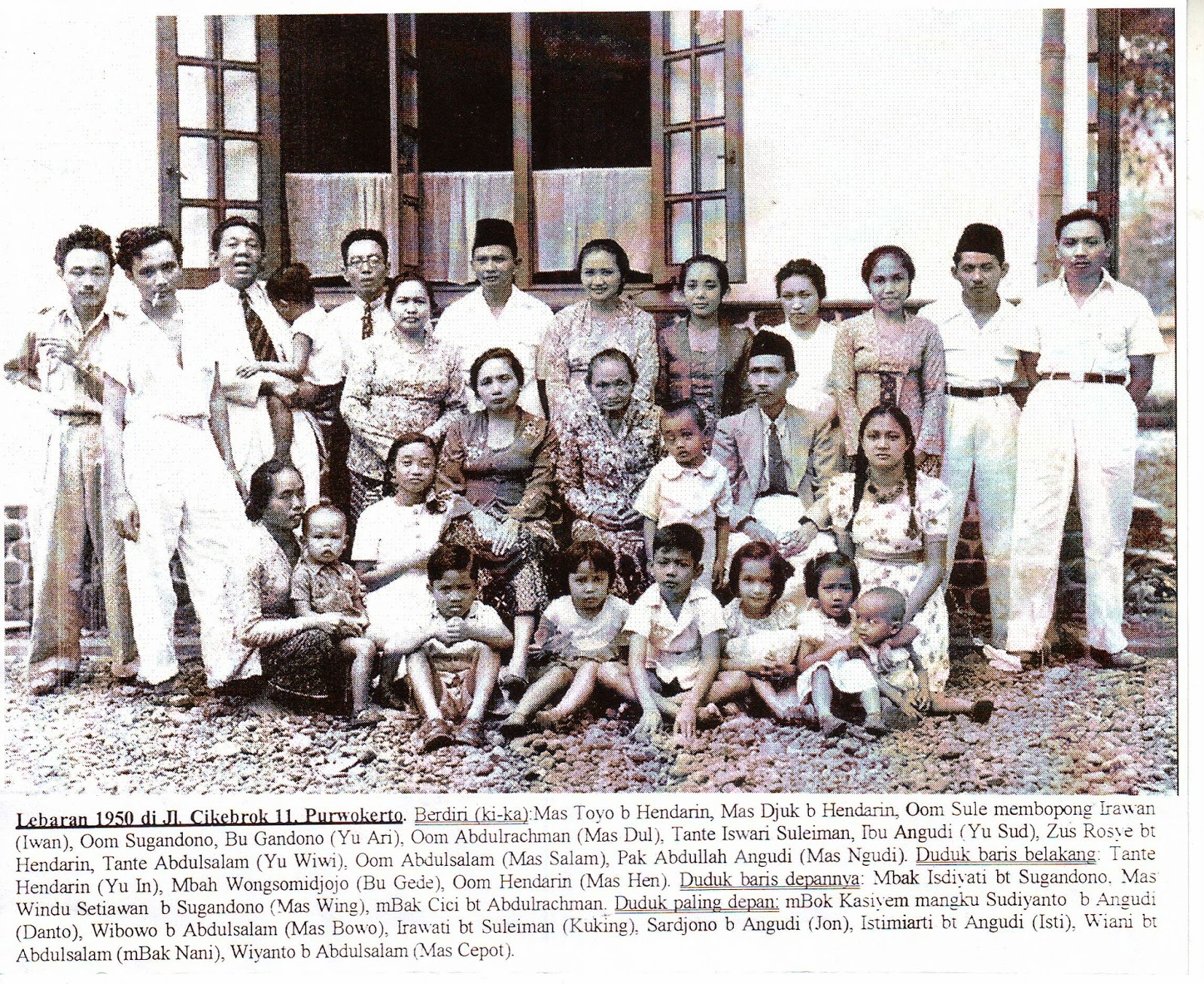

One year after the war. Arrestee: Abdullah Angudi and Abdulsalam (1st and 2nd from right).The writer sit at front 4th from right.

References:

id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perjanjian_Renville

id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perundingan_Linggarjati

id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agresi_Militer_Belanda_I

id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agresi_Militer_Belanda_II